In 2015, I was beginning first to explore complex systems, and I discovered System Dynamics. When people talk about systems thinking with any modeling rigor, they often mean Systems Dynamics. It is often considered an approach to dealing with complexity, even though this, and most other systems approaches, are most applicable when things are complicated and not when they are complex.

Systems Dynamics became part of the leadership lexicon with Peter Senge’s book The 5th Discipline. Another classic worth reading is Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows. If people are curious to hear more, I am happy to share my thoughts and notes on these books. But for now, I will stick to the subject of Systems Dynamics itself.

Thinking systemically generally means understanding the larger picture and the multiple interrelationships within a system. System Dynamics is an approach for creating models to help show what is happening in a system. These models generally consist of Causal Loop Diagrams and Stock flow Diagrams.

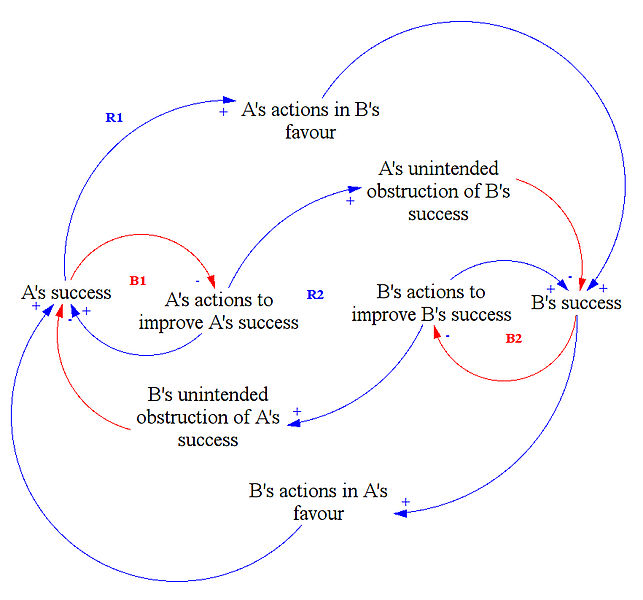

Causal Loop Diagrams show how changes in one variable influence other variables. The influence can drive change in the same direction. More satisfied customers lead to more word-of-mouth references which lead to more sales.

When this is drawn as a loop, it is called reinforcing as the positive change of each variable leads to positive changes in the others (this also works negatively. Less satisfied customer leads to less word-of-mouth…).

Another type of loop is a balancing loop, in which the change in one variable leads to the opposite change in another. More customers using your product in a market leads to fewer possible new customers in that market.

The third detail is delay; not all changes happen immediately. If you think about managing the water temperature out of a faucet: you sense the water is too cold and turn it up, then you wait while the temperature changes. The longer the delay, the more likely you are to change the temp again before it has settled at the new temperature and to overshoot the desired temperature.

Finally, stock and flow diagrams show the number of things and the rate of change between them. A great example would be potential customers becoming customers, which is very similar to the dynamics of a sales funnel. The stock is the number of potential and new customers, and the rate of change is the flow from potential to new.

With these four building blocks, you can build quite complicated models. These diagrams help model everything from sales cycles to environmental change and epidemics. In addition, several archetypes of systems seem to occur frequently, such as limits to growth, shifting the burden, and the tragedy of the commons.

These models can be useful for understanding complicated systems where causal relationships can be defined in advance and where many variables exist. They are good tools for helping others understand systems thinking generally and aiding discussions about the variables impacting a system. These systems lend themselves to computer modeling, which can be useful for predicting outcomes. The archetypes can be useful guides for managers regarding things to watch out for and help them to identify systemic patterns.

However, there are limits. The direct cause-and-effect relationship of the models means that they are deterministic and don’t work well where cause and effect cannot be known, for example: when things are complex. While the archetypes are useful patterns, they are never likely to appear in the simple forms described.

There are other challenges as well. There is also a desire to be able to view these systems as an outside observer, but in reality, that is not possible. We are all within the systems and must understand our viewpoints’ limitations. There will always be questions about what is included and left out of these models. These exclusions are challenging in social situations where power dynamics influence the modeling. As a result, the models are also reductionist and key information can be left out when the causal links are unknown. Additionally, people are never as consistent or predictable as a model like this would imply.

If you are new to thinking about systems, I recommend Thinking in Systems as a great book to start your journey. Still, I warn you that most proponents of this approach downplay the limitations and make bold claims with almost religious zeal, so it is good to look at them critically.