I will admit it: I am an AI skeptic. But that said, I recently spent some time building a project with AI, and I was impressed. Still, I believe some of AI’s promises are overstated. AI will continue to improve, but I don’t believe the risk to humans is an Artificial General Intelligence that will destroy the world. I think that AI as it exists can do that, not because it has some super intelligence but merely through the environmental costs and the societal harm of diminishing critical thinking skills, widening income disparity, and increasing job precarity that automation on this scale can cause. In this newsletter, I won’t look at all these issues, but I will want to touch on my experience with AI and try to put it in a larger historical context. That said, I am not an AI expert, and I would defer to people like Melanie Mitchell to explain the capabilities and limitations of AI.

For a while, I have been using some AI. I used the basic level of AI built into Grammarly to help me be a better writer by fixing my grammatical and spelling errors and simplifying my sentences (although I ignore as many suggestions as I accept). I enjoy “ chatting” with the highlight of all the books I have read through Readwise, making research for my writing more manageable. But recently, I tried something else.

I built an app to maintain a content schedule and automatically post to LinkedIn1.

Using a combination of Claude, ChatGPT, Google Gemini, and Cursor, I created a fully functioning app in about 10-12 hours. What was impressive is that I had never written anything meaningful in React before and had only used node.js briefly more than 7 years ago. However, I have spent half of my career as an engineer, so I started from a solid understanding of what should work and how to write good code.

I learned that building things using AI makes you more efficient, but you do have to understand how to code. I spent most of my time debugging changes that the AI made. There were times where the fix was so obvious, and yet, the AI just couldn’t resolve it, and there were probably 5 or 6 times where an update the AI made completely broke everything. Had I not had my code in source control and been committing after every successful update, I might have had to start from scratch. Additionally, the code initially produced was a rat’s nest, and if I hadn’t known about good coding practices, the code would have been unmanageable. Still, what I could do was faster and easier than if I had tried to do it alone.

Ultimately, it felt like William Haber in Lathe of Heaven, trying to control George Orr’s dreams and design a utopia. You might think the prompt was correct, but the slightest ambiguity or miswording can lead to unexpected (usually harmful) consequences. Ultimately, it felt like micromanaging a junior engineer; if I told it exactly what I wanted and how to accomplish the task, the AI could build the feature far faster than I could.

Why am I telling you all this on a blog about being a middle manager?

Because the current stage of AI is something that managers need to wrestle with, I think there is an angle that doesn’t get enough attention. At the same time, lots of people are trying to divide the world into those who are for or against AI, but there needs to be more nuance than that. I want to show that it is possible to recognize AI’s value while having legitimate concerns about what this means. I also don’t want to come at this as someone who hasn’t tried the tools and is merely challenging it intellectually. I wanted some grounding in what is possible today in a field I understand. And, because, when I say next that I think we can learn from the Luddites, I want you to realize that I am not coming from a place of fear or ignorance about the technology. Which is what people typically associate with the term Luddite.

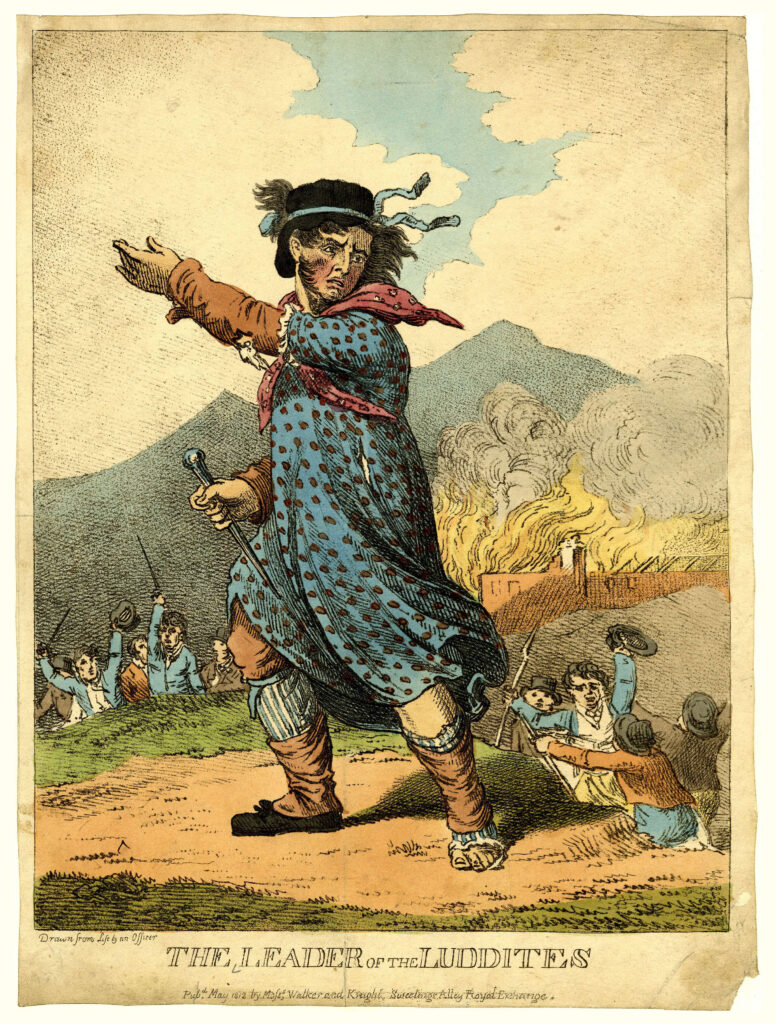

Who Were the Luddites?

The Luddites were a group of textile weavers who protested using new machines that automated weaving. Laws had recently been passed that banned Trade Unions, so the workers took up a new strategy. 2

Between 1811 and 1812, hundreds of new frameworks were destroyed in dozens of coordinated, clandestine attacks under the aegis of a mythical leader called “Ned Ludd.” In addition to their notorious raids, the so-called Luddites launched vociferous public protests, sparked chaotic riots, and continually stole from mills—activities all marked by an astonishing level of organized militancy. Their politics not only took the form of violent activity but was also enunciated through voluminous decentralized letter-writing campaigns, which petitioned—and sometimes threatened—local industrialists and government bureaucrats, pressing for reforms such as higher minimum wages, cessation of child labor, and standards of quality for cloth goods. The Luddites’ political activities earned them the sympathies of their communities, whose widespread support protected the identities of militants from the authorities. At the height of their activity in Nottingham, from November 1811 to February 1812, disciplined bands of masked Luddites attacked and destroyed frames almost every night. Mill owners were terrified. Wages rose. 3

Today, we think of the Luddites often as anti-machine, anti-technology, or anti-progress, but as Gavin Mueller explains:

Luddism, inspired as it is by workers’ struggles at the point of production, emphasizes autonomy: the freedom of conduct, ability to set standards, and the continuity and improvement of working conditions. 4

These are essential ideas to consider as the wave of AI-based automation comes for knowledge workers.

Labor Savings

AI, like many forms of automation before us, has been based on the idea that it will save time and make us more efficient, and in a way, it does. My project took me far less time than it would have if I had to write all the code myself. AI promises that these tasks and some other jobs could be done automatically for us. So, what is the issue? We all want to save time. The problem is that the promise of AI isn’t really about saving labor. It is about skill diminishing. If we look at this historically, this was always the claim of automation.

They are called “labour-saving” machines—a commonly used phrase which implies what we expect of them; but we do not get what we expect. What they really do is to reduce the skilled labourer to the rank of the unskilled, to increase the number of the “reserve army of labour”—that is, to increase the precariousness of life among the workers and to intensify the labour of those who serve the machines (as slaves their masters). 5

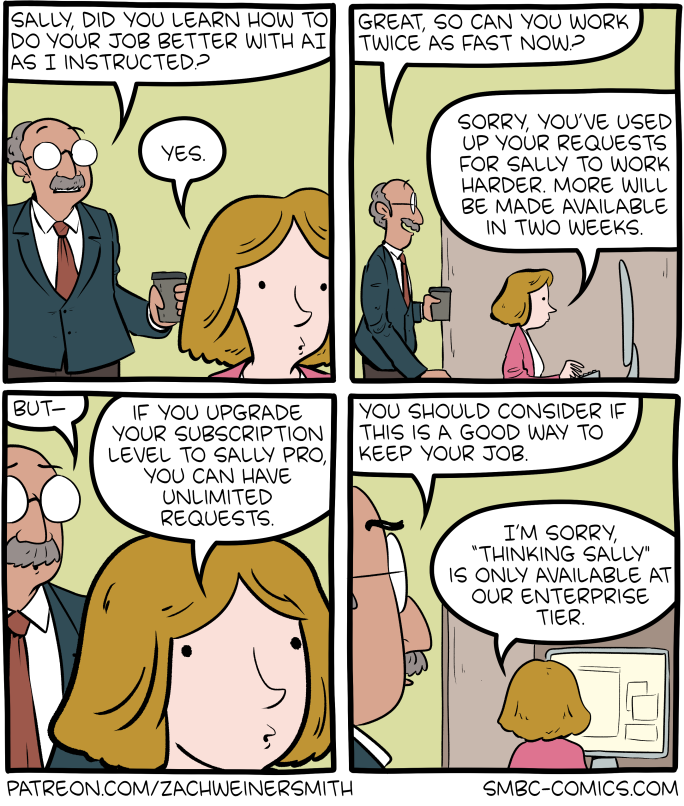

The technology is not at this point yet for coding, at least. But what it does do is change the nature of the job. You don’t need as many coders, and the ones you need are the ones that can think at a higher level to explain what things are. Mark Zuckerberg claimed he no longer needs mid-level engineers, and I understand where he is coming from. Junior engineers can now do much of the grunt work, and the more senior engineers can guide and debug. The problem is where future senior engineers will come from and how the junior engineers will learn and grow.

The goal of this technology is to make many roles replaceable with AI. Imagine a world where one manager could manage multiple AI bots working on different features or projects and debugging and guiding the code development.

And this is, in some ways, reminiscent of a shift that came with previous automation.

At the turn of the century, it was the workers, rather than their overseers, who understood how manufacturing worked, and their methods for completing tasks were often based on intuitive and informal “rules of thumb”: what color a chemical admixture should take, the appropriate heft of a specific part, and the like. Factory owners and managers might have only a dim idea about how products were actually put together, and no ability to do it themselves. This control of knowledge meant that workers could control the pace of work. Out of desire or necessity, they could slow it down, even stop it altogether.6

This has been the general push of scientific management. Scientific management is trying to use the scientific method to improve efficiency. The goal is to maximize the work produced with the fewest workers.

Scientific management, for all its pretensions, was less about determining ideal working methods and more about shattering this tremendous source of worker power. By breaking apart each work process into carefully scrutinized component tasks, Taylor had cracked the secret of labor’s advantage, thereby giving management complete mastery over the productive process.7

It is now easy to see how this move to AI mirrors base changes in the world of work. Perhaps the most significant change is that while the previous automation and scientific management approaches primarily came for blue-collar workers, AI is from white-collar knowledge workers. These workers have long thought they are immune to this sort of change. Yes, of course, they could be let go when the economy goes south, or for the greed of the CEO, or that their job could be off-shored, but the role itself would be needed.

We should go back to John Maynard Keynes’ prediction, “In 1930, John Maynard Keynes published a short essay entitled ‘Economic possibilities for our grandchildren’. It is famous (notorious?) for its prediction that a hundred years hence, people would work for only 15 hours per week.” 8

David Autor, an economist, offers a useful corrective to this mistake in his 2015 article “Why Are There Still So Many Jobs?,” its plaintive title a response to John Maynard Keynes’s rosy predictions of a future with a reduced work week. As Autor explains, rather than simply replace human jobs with machinic processes, automation affects labor in complex ways:

Changes in technology do alter the types of jobs available and what those jobs pay. In the last few decades, one noticeable change has been “polarization” of the labor market, in which wage gains went disproportionately to those at the top and at the bottom of the income and skill distribution, not to those in the middle. 9

As I saw when building my app with AI, and as Zuckerberg has called out, AI is moving jobs out of the middle and towards the lower and higher end of the spectrum.

When people say AI is not going to take your job, someone using AI is they are partially correct. At the top end of the job market, those with significant skills and experience who leverage AI will still play essential roles, but those roles will change, those in the middle will likely lose their jobs to more junior people who can use AI.

A Benefit for Small Businesses

AI will enable more individuals to create businesses and do more than possible. This can lead to more people working for themselves and gaining freedom from large employers. I think there can be many more small businesses that grow from this approach, and there can be a real benefit.

While AI has benefits and what it means for small businesses, there is also a significant catch. There is a term thrown around a lot for this current state of capitalism called Techo-Feudalism, and while I think that advocates of it often overstate the relevance. The idea of small companies built on AI (paying fees to AI companies for those services) and leveraging cloud technology to sell services (and paying more fees to those cloud providers) very much begins to look like a feudal society where producers are dependent on these larger feudal lords and return a percentage of all they make to those lords.

Giving Workers Control of AI

Ultimately, AI will be most valuable if workers can gain control of how AI is used and what it means for their roles. This is very much what the Luddite movement tried to do for the technological advances of its time.

Luddism contains a critical perspective on technology that pays particular attention to technology’s relationship to the labor process and working conditions. In other words, it views technology not as neutral but as a site of struggle. Luddism rejects production for production’s sake: it is critical of “efficiency” as an end goal, as there are other values at stake in work. 11

The utopian dream of AI should improve everyone’s quality of life, with fewer hours of work required to make an adequate living. It is doubtful that existing technology could facilitate such an outcome, and for that to be possible as technology progresses, there will need to be a more significant shift in how we relate to work. Work is and always has been about knowledge production. As Matteo Pasquinelli talks about in his social history of AI The Eye of the Master:

[A]ll labour, without distinction, was and still is cognitive and knowledge-producing. The most important component of labour is not energy and motion (which are easy to automate and replace) but knowledge and intelligence (which are far from being completely automated in the age of AI). The industrial age was also the moment of the originary accumulation of technical intelligence as the dispossession of knowledge from labour. AI is today the continuation of the same process: it is a systematic mechanisation and capitalisation of collective knowledge into new apparatuses, into the datasets, algorithms, and statistical models of machine learning, among other techniques.12

The ability to produce new knowledge will be required more than ever in a world of AI, and it won’t change. AI will be a tool we can use in that process, but it can’t replace the knowledge production itself. How we continue to produce knowledge and relate to these tools will define what they become.

In the twentieth century, in other words, it was not information technologies that primarily reshaped society, as the mythologised vision of the ‘information society’ implies; rather, it was social relations that forged communication networks, information technologies, and cybernetic theories from within. Information algorithms were designed according to the logic of self-organisation to better capture a social and economic field undergoing radical transformation. 13

In the end, it won’t be AI that reshapes society, but society that will shape AI. What we choose to see as automatable, where we decide to add vs remove critical thinking, are the choices that will shape what AI will become. This is already happening.

By implicitly declaring what can be automated and what cannot, AI has imposed a new metrics of intelligence at each stage of its development. But to compare human and machine intelligence implies also a judgement about which human behaviour or social group is more intelligent than another, which workers can be replaced and which cannot. Ultimately, AI is not only a tool for automating labour but also for imposing standards of mechanical intelligence that propagate, more or less invisibly, social hierarchies of knowledge and skill. As with any previous form of automation, AI does not simply replace workers but displaces and restructures them into a new social order.14

Workers must be involved in making choices about what and how we automate with AI. The answer is not to try to destroy AI or to assume that it can solve all of our problems, but rather, we need to ensure that we retain human agency and intelligence. The solutions are not to be found in the technology but in the social and political spheres.

What is needed is neither techno-solutionism nor techno-pauperism, but instead a culture of invention, design and planning which cares for communities and the collective, and never entirely relinquishes agency and intelligence to automation. The first step of technopolitics is not technological but political. It is about emancipating and decolonising, when not abolishing as a whole, the organisation of labour and social relations on which complex technical systems, industrial robots, and social algorithms are based – specifically their inbuilt wage system, property rights, and identity politics. 15

What Does this mean for Middle Managers?

We are still in the early stages of AI development; we don’t know its real costs, and the technology has significant weaknesses. At the same time, it can dramatically change what is possible for employees.

Allow your teams and individuals to lead the way with AI as much as possible. There are security, privacy, and data concerns that may need to be handled at an organizational level, such as what can be used, but to use it or not and how should be up to the teams.

One way to look at an ideal outcome is that your teams can automate the work they find to be a grind, focus on what they enjoy, accomplish more, and work less. But that can only happen when we allow those closest to the technology to make the choices.

- Yes, other things do this. I tried using Taplio for a while, but I couldn’t justify the ridiculous price tag, which is again based on AI features. If anyone is interested in a cheap service to run a content scheduler, let me know, and I may make this more generally available. ↩

- Gavin Mueller, Breaking Things at Work: The Luddites Are Right About Why You Hate Your Job ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Nicholas Crafts, The 15-Hour Week: Keynes’s Prediction Revisited ↩

- Gavin Mueller, Breaking Things at Work: The Luddites Are Right About Why You Hate Your Job ↩

- https://www.smbc-comics.com/comic/ai-14 ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Matteo Pasquinelli, The Eye of the Master: A Social History of Artificial Intelligence ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩